An expanded version of this post was published as:

Smart, John M., Humanity Rising: Why Evolutionary Developmentalism Will Inherit the Future, World Future Review, November 2015: 116-130. doi:10.1177/1946756715601647 (SAGE: abstract). Oct 2016:

Full PDF (21 pages) is now available here.

For more on Evo-Devo, see Chapter 11 (Evo-Devo Foresight) of my online book, The Foresight Guide (2018).

What is evolutionary development (“evo-devo”)? It is a minority view of change in science, business, policy, foresight and philosophy today, a simultaneous application of both evolutionary and developmental thinking to the universe and its replicating subsystems. It is derived from evo-devo biology, a view of biological change that is redefining our thinking about evolution and development. As a big picture perspective on complex systems, I think evo-devo models will be critical to understanding our past, present, and future. The sixty-some scholars at Evo-Devo Universe, an interdisciplinary community I co-founded with philosopher Clement Vidal in 2008, are interested in arguing, critiquing and testing evolutionary and developmental models of the universe and its subsystems, and exploring their variations and implications.

Whatever else our universe is, and allowing that there are physical mysteries, like dark matter, dark energy, the substructure of quarks, and the nature of black holes still to be uncovered, reasonable analysis suggests that it is both evolutionary and developmental, or “evo-devo”. Like a living organism, it undergoes both experimental, stochastic, divergent, and unpredictable change, a process we can call evolution , and at the same time, programmed, convergent, conservative, and predictable change, a process we can call development. Evo-devo thinking is practiced by any who realize that parts of our future are unpredictable and creative, while other parts are predictable and conservative, and that in the universe, as in life, both processes are always operating at the same time.

Like living organisms, our universe may have a developmental life cycle.

Our universe builds intelligence in a developmental hierarchy as it unfolds, from physics, to chemistry, to biology, to biominds, to postbiological intelligence. As physicists like Lee Smolin (The Life of the Cosmos, 1999) have argued, our universe may also be chained to a developmental life cycle, like a living organism. Since almost every interesting complex system we know of within the universe, from solar systems to cells, undergoes some form of replication, inheritance, variation, and selection to build its complexity, it is parsimonious (conceptually the simplest model) to suspect this is how the universe built its complexity as well, within a still poorly understood environment that physicists call the multiverse.

An evo-devo universe proposes that any physical system that has both evolutionary (divergence, variation) and developmental (convergence, replication, inheritance) features, and operates in a selective environment, will self-organize its own adaptive complexity as replication proceeds. Consider how replicating stars have advanced from the primitive Population III stars to the far more complex Population I solar systems, like our Sun and its complex planets, over galactic time. Replicating evo-devo chemicals built up from nucleic acids to cells, over billions of years. Replicating evo-devo cells created multicellular life with nervous systems, again over billions of years. Replicating evo-devo nervous systems forged hominids, over roughly 500 million years. Replicating languages, ideas, and behaviors in hominid brains birthed nonbiological computing systems, over something like 5 million years. Now computing and robotics systems, whose replication is presently aided by human culture, are soon (within the next few decades, it seems) going to be able to replicate, evolve, and develop autonomously.

The evo-devo model provides an intuitive, life-analogous, and conceptually parsimonious explanation for several nagging and otherwise improbable phenomena, including the fine-tuned Universe problem, the presumed great fecundity of terrestrial planets and life, when an evolution-only framework would lead us to predict a Rare Earth universe, the Gaia hypothesis, the surprisingly life-protective and geohomeostatic nature of Earth’s environment, the unreasonably smooth, redundant and resilient nature of accelerating change and leading-edge complexification on Earth, and other curiosities. If true, it should be able to increasingly demonstrate how and why such phenomena might self-organize as strategies to ensure a more adaptive and intelligence-permitting universe, in an ultimately simulation testable model. It also provides a rejoinder to theologian William Paley’s famous watchmaker argument, that only a God could have designed our planet’s breathtaking complexity, with the curious example of replicative self-organization of complexity, a phenomenon seen in a great variety of dissipative systems on multiple scales in our universe, and one we will increasingly understand, model, and test in coming years.

As much as some might find comfort in believing in a God who designed our universe, it is perhaps even more comforting to believe, tentatively and conditionally, in a Universe with such incredible self-organizing and self-protecting features, and in the amazing history and abilities of evolutionary and developmental processes in living systems themselves. Evo-devo processes have apparently created both matter and mind, and have been astonishingly resilient to generating complexity and intelligence at ever-accelerating rates. Found throughout our universe, such information-protective processes may even transcend our universe, and may have determined the first replicator, if such a thing exists. Then again, perhaps our physics and information theory will never reach back that far, and such knowledge may forever remain metaphysics. In the meantime we can say that Big History, the science story of the universe so far, is sufficiently awe inspiring, humbling, useful, and hopeful to give us guidance, once we place it in an evo-devo frame. As we’ll suggest, we now know enough about evolution and development at the universal scale to begin relating these processes to our own lives, and most interestingly, to ask how we can make our values and goals more consistent with universal processes.

As our universe grows islands of accelerating local order and intelligence in a sea of ever-increasing entropy, physics tells us this process cannot continue forever. The universe’s “body” is aging, and will end in either heat death, or a big rip, or both. If our universe is indeed a replicating complex adaptive system that engages in both evolution and development, as it grows older it must package its intelligence into some kind of reproductive system, so it’s complexity can survive its death and begin again. Developmental models thus argue that intelligent civilizations throughout the universe are part of that reproductive system – protecting our complexity and ultimately reproducing the universe and further improving the intelligence it contains. In other words, growing, protecting, and reproducing personal, family, social, and universal intelligence may be the evolutionary developmental purpose of all intelligent beings, to the greatest extent that they are able.

Beginning in 1859, Charles Darwin helped us to clearly see evolutionism in living systems, for the first time. Discovering that humanity was an incremental, experimental product of the natural world was a revolutionary advance over our intellectually passive, antirational and humanocentric religious beliefs. But until we also understand and accept developmentalism, recognizing that the universe not only evolves but develops, the purpose and values of the universe, and our place in it will remain high mysteries about which science has little of interest to say. Our science will remain infantile, descriptive without also being prescriptive, and unable to deeply inform our morality and politics. That must and will change in coming decades.

As an example of where we are today, I just watched a Discovery Channel program on evolution, Mankind Rising, available for $1.99 at YouTube. It is Season 2, Episode 8 of Curiosity a new educational television series launched by Discovery founder and chairman John Hendricks. Curiosity is a five-year, multi-million dollar initiative to tackle fundamental questions and mysteries of science, technology, and society, in sixty episodes. There is also a commendable Curiosity initiative in American K-12 schools, to use the show to increase our children’s engagement in STEM education.

Mankind Rising – Season 2, Episode 8 of Curiosity

Mankind Rising considers the question “How did we get here?” It tells the journey of humanity from the cooling of life’s nursery, Earth, 4 billion years ago, and the emergence of the first cell 3.8 billion years ago, to Homo erectus, anatomically modern humans, 1.8 million years ago. It does this in one 43 minute time-lapsed computer animation, the first time our biological history has received such a treatment, as far as I know. The animation is primitive, but it holds your interest enough to follow the story. And what an amazing story it is. We see a lovely visualization of the Phylogenetic hypothesis, which proposes that human hiccups are a holdover from our amphibian ancestry, when we gulped air at the surface across our gills, which are now vestigial (think of pharyngeal pouches in human embryos), before we grew lungs. Human babies do a lot of gulping-hiccuping both in utero and when born prematurely, and both amphibian gill-gulping and human hiccups are stopped by elevated carbon dioxide, hence the folk remedy to breathe into a bag to stop them.

We also get to see the rise of the first tool users, Homo habilis, 4 million years ago, in a dramatic sequence where an early human strikes one rock against another and is fascinated to discover a sharp rock in his hands. H. habilis’ ability to hold sharp rocks and clubs in their hands, and use them imitatively in groups to defend against other animals was perhaps the original human event. The best definition of humanity, in my opinion, is any species that gains the ability to use technology creatively and socially to continually turn themselves into something more than their biological selves. We inevitably become a species with both greater mind (rationality, intellect) and greater heart (emotion, empathy, love), two core kinds of intelligence. I would predict the first collaborative rock-users on any Earth-like planet must soon thereafter become its dominant species, as there are so many paths to further adaptiveness from the powerful developmental duo of creative tool use and socially imitative behavior.

Homo habilis, perhaps the first persistence hunters.

One clever thing that the first socially-adept rock- and club-holding animals on any Earth-like planet gain access to is pack hunting (and if good at sweating, a form of pack hunting called persistence hunting). Learning both how to pack hunt and how to tame fire, as described in Richard Wrangham’s Catching Fire: How Cooking Made Us Human, 2010, may have doubled our brain size by giving us our first reliable access to meat, a very high-energy fuel source. We may have begun with pack hunting by ambush, which chimpanzees do today, and then graduated to persistence hunting, or running down our prey, sometimes in combination with setting fires to flush out our prey. We primates sweat across our entire bodies, not just through our mouths like other mammals. Humans have developed our sweating and cooling ability the best of all primates by far. As a result, two or three of us working together can actually run to heat exhaustion any animals that can’t sweat, if we hunt them in the mid-day sun. Some peoples persistence hunt even today, as seen in this amazing seven minute Life on Earth clip of San Bushmen running down a Kudu antelope (!!) in the Kalahari desert. Mankind Rising ends with Homo erectus (“human upright”), possibly the first language-using humans, 1.8 million years ago. We don’t yet have fossil evidence their larynx was anatomically modern, but there are indirect arguments. Language, both a form of socially imitative behavior and a fundamental tool for information encoding and processing, was very likely the final technology needed to push our species from the animal to the human level.

In Evolutionism, the Universe is a Massive Set of Random Events, Randomly Interacting.

Unfortunately, there are serious shortcomings to Mankind Rising as an educational device. The show’s narrative, and the theory it represents, are the standard one-sided, dogmatically-presented story of life’s evolution, with no hint of life’s development. As a result, it treats humanity’s history as one big series of unpredictable accidents. This is the perspective of universal evolutionism, also called “Universal Darwinism” ”, which considers random selection to be the only process in universal change, ignoring the possibility of universal development. In evolutionism, all the great emergence events are told as happening randomly and contingently. The show even makes the extreme claim that life itself emerged “against the laws of probability.” The emergence of humanlike animals is also presented as a stroke of blind luck, because the K-T meteorite wiped out our predators, the dinosaurs. All of this is true in part, only from one set of perspectives, that of the individual, organism, or individual event. In other words this story, and evolutionism in general, is a dangerously incomplete half-truth.

When we look at the same events from the perspective of the universal system, the environment, or distributions of events over time, we can easily argue that many particular forms and functions appear physically predetermined to emerge. Consider two genetically identical biological twins, or two snowflakes. Most of what happens to them up close, at the molecular scale, is randomly, contingently, unpredictably different. The microstructure of all the twin’s organs, including their brain, fingerprints, and many other molecular features are as different as the designs on two snowflakes. But look at them from across the room, taking a system or environmental perspective, and you see that they achieve many of the same developmental endpoints over time. The twins have the same body and facial structure and many of the same personality traits, constrained by the organism’s developmental genes and the shared environment. The snowflake’s hexagonal structure is developmentally predetermined, constrained by the way water forms hydrogen bonds as it freezes.

Just like biological development, universal development happens because of the special initial conditions (physical laws, or “genes”) of our universe, the time constancy and environmental sameness (isotropy) of some physical law throughout the universe/system/environment, and the apparent commonness (ubiquity) of Earth-like planets in our universe, a suspicion that will hopefully be proven by astrobiologists in coming years. Examples of developmental processes and structures are easy to propose. We can see developmental physics in the motions of the planets, which are highly future-predictable, as Isaac Newton discovered. Other physical processes, such as the production of black holes in general relativity, the acceleration of entropy production, and of complexification in special locations, also appear highly predictable and universal. Other physics by contrast, such as quantum physics, looks highly evolutionary and unpredictable. As we move up the complexity hierarchy from physics to chemistry to biology, to society, our list of potential evolutionary and developmental forms and processes rapidly grows.

In Developmentalism, Certain Universal Forms and Functions are Statistically Fated to Emerge, as in Biological Development

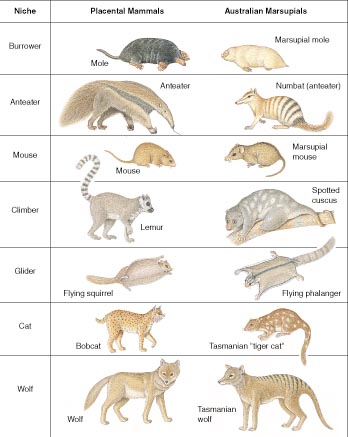

Convergent form and function in placental and marsupial mammals – a famous example of convergent evolution, or better, convergent evolutionary development.

Other examples of inevitable, ubiquitous developments in our universe may include organic chemistry as the only easy path to complex replicating autocatalytic molecular species. Earth-like planets with water, carbon and nitrogen cycles (plate tectonics), nucleic acids, lipid membranes, amino acids, and proteins as the only easy path to cells (testable by simulation). Oxidative phosphorylation redox chemistry as the only easy path to high-energy chemical life. Multicellular organisms, bilateral symmetry, eyes, skeletons, jointed limbs, land colonization, opposable thumbs, social brains, gestural and vocal language, and imitative behavior as the only easy path to runaway technology (tool use). And similar unique developmental advantages to written language, math, science, and various technology archetypes, from sharp rocks and clubs to levers, wheels, electricity, and computers. These potentially universal forms and functions may be destined to emerge, because of the particular initial conditions and laws of the universe in which evolution is occurring, and each are destined to become optimal or dominant, for their time, in environments in which accelerating complexification and intelligence growth are occurring.

On Earth, we have seen a number of these forms, such as eyes, emerge and persist independently in various separate evolutionary lineages and environments. Independent emergence, convergence, and optimization or dominance of developmental forms and processes is one good way to separate them from the much larger set of ongoing evolutionary experiments. Developmental forms and functions are those that will be more adaptive at each particular stage of environmental complexity, in more contexts and species. Think of two eyes for a predator, over three or one eye. Or four wheels for a car, over three or more than four wheels. Or all the body form and function types that converged in placental and marsupial mammals. Australia separated early from the other continents, yet produced many similar mammal types via marsupials, plus a few new ones, like the kangaroo. This is a classic example of convergent evolution, or more accurately, convergent evolutionary development, when we examine biological change from the planet and universe’s perspective.

Evolution is destined to randomly, contingently, and creatively but inevitably discover these optimal developmental forms and functions, in most environments. For more on evolutionary developmentalism, feel free to read my 50-page precis, Evo Devo Universe?, 2008, and let me know your thoughts.

Would Raptors Have Led Inevitably to Dinosaur Humanoids (Dinosauroids), if the K-T Meteorite Hadn’t Hit 65 Mya? That is the Dinosauroid Hypothesis, a Developmentalist Proposal.

As another example ignored by the show, several evolutionary developmentalists have independently proposed that our very-easy-to-create-yet-general-purpose “humanoid form”, a bilaterally symmetric bipedal tetrapod with two eyes and two opposable thumbs, is a very likely outcome for all biological intelligences that first achieve our level of sophistication on all Earth-like planets. If we saw such “early” alien intelligences from across a dimly lit room, they would they look roughly like us, as the astrophysicist Frank Drake, author of the Drake equation, has argued. But while we can use science and simulation to argue their existence, in my view we have virtually no chance to meet other biological organisms in the flesh. Why? Because the universe does a very good job of separating all the evolutionary experiments by vast distances, uncrossable by biological beings. Our universe may have self organized to have its current structure in order to maximize the diversity of intelligences created within it, as I argue in my 2008 paper. No intelligence is ever Godlike, so diversity is our best strategy for improving our lot. Another reason we’ll likely never meet biological beings from other Earthlike planets is because the leading edge of life on Earth is now rapidly on the way to becoming postbiological, and postbiologicals are likely to have very different interests than traveling long distances through slow and boring outer space, when there are much better options apparently available in “inner space,” as I argue in my 2012 paper.

In other words, our own particular mammalian pathway to higher intelligence has likely given us a unique evolutionary pathway to our developmental humanity, one with great universal value. Our civilization has likely discovered and created some things you won’t find anywhere else in the universe. But at the same time, if the K-T meteorite hadn’t struck us 65 mya, it is easy for an evolutionary developmentalist to argue that dinosaurs like Troodon would have inevitably discovered the humanoid form, rocks, language, and tools, and we might have looked today like that green-skinned humanoid in the picture above. Why?

If you have seen the movie Jurassic Park, or have read up on raptors like Troodon, you know that they had semi-opposable digits and hunted in packs, in both the day and the night. It is easy to bet that the first raptor descendants that also learned how to hold sharp rocks and clubs in their hands in close-quarters combat would have forever after owned the role of top biological species. It would be game over, and competitive exclusion, for all other species that wanted that niche. Once you are manipulating tools in your hands, and speaking with your larynx, it’s easy to imagine that your body is forced upright, and your tail is no longer useful. You are engaged in runaway complexification of your social and technical intelligence – you’ve become human, and the leading edge of local planetary intelligence has jumped to a higher substrate. Dale Russell, author of the Dinosauroid hypothesis in 1982, was scoffed at by conventional evolutionists back then, and the model is still largely ignored today, see for example Wikipedia’s short and evolutionist-biased paragraph on it. This response from the scientific community is predictable, given the hornet’s nest of implications that evolutionary developmentalism introduces, including all the deficiencies in current cosmology of our understanding of the roles of information, computation, life and mind.

Note the closeup of the hand of Stenonychosaurus (now called Troodon) inequalis, from Russell’s paper,“Reconstructions of the small cretaceous theropod Stenonychosauris inequalis and a hypothetical dinosauroid,” Dale A. Russell and Ron Séguin, Syllogeus, 37, 1982. The authors state the structure of the carpal block on Troodon’s hands argues that one of the three fingers partially opposed the other two as shown. The shape of the ulna also suggests its forearms rotated. It probably used its hands to snatch small prey, and to grab hold of larger dinosaurs while ripping into them with the raptorial claw on the inside of each of its feet. Troodon was a member of a very successful and diverse clade of small bipedal, binocular vision dinosaurs with one free claw on their feet, the Deinonychosaurs (“fearsome claw lizards”). These animals lived over the last 100 million years of the 165 million years of dinosaur existence, and were among the smartest and most agile dinosaurs known, with the highest brain-to-body ratios of any animals in the Mesozoic era. Most Deinonychosaurs had arms that were a useful combination of small wings and crude hands consisting of three long claws. Troodon was in a special subfamily that had lost the wings but retained the three long digits on each hand. According to Russell, Troodon’s brain-to-body ratio was the highest known for dinosaurs at the time. Because of their special abilities, I would argue that Deinonychosaurs were not only members of an evolutionarily successful niche, they also occupied an inevitably successful developmental niche as well.

The assumption here, made by a handful of anthropologists and evolutionary scholars over the years, is that trees are a key niche, the “developmental bottleneck,” through which the first rock-throwing and club-wielding imitative hominids will very likely pass, on a typical Earth-like planet. Swinging from limb to limb requires very dextrous hands, and just as importantly, a cerebellum and forebrain that can predict where the body will go in space. With their manipulative hands, with or without wings, their big, strong legs and multipurpose feet, yet their small size, Deinonychosaurs would have been impressive tree climbers, able to get rapidly up and down from considerable heights. If they were the largest and strongest animals physically capable of doing so, which seems likely, this argues that they would have permanently occupied the special niche that primates would later inhabit. Imagine primates trying to get into the all-important tree niche with Deinonychosaurs running about. Good luck! Deinonychosaurs would have achieved “competitive exclusion”, the ability to permanently deny other species access to the critical transitional niche that was the gateway to significantly more intelligent and adaptive life. Much later, Homo sapiens achieved competitive exclusion by being the first to achieve runaway language and tool use, using these to deny all other primates access to more intelligent and adaptive social structures, including our closest competitors, Homo neanderthalensis and others.

So if tree climbing and swinging is the fastest and best way to build grasping hands and predictive brains good at simulating complex trajectories (a claim testable by future simulation) and eventually, modeling and imitating the mental states of others in their pack so they could do imitative tool use (the next critical developmental bottleneck leading to planetary dominance for the first species to do so, also testable by future simulation), then if Deinonychosaurs dominated that niche, it is reasonable to expect a Deinonychosaur to be the first to make the jump to tool use. Troodon couldn’t swing in the trees, but he would have been very agile among them, able to use them for escape and evasion. He had two manipulative hands that would have been very useful both in killing and in avoiding being killed. This looks to me like a potential case for competitive exclusion. The hypothesis to test is that tree environments are the dominant developmental place on land to breed smart, socially-imitative and tool-using species, just as land appears to be the dominant developmental place for the emergence of species that use built structures, on any Earth-like planet.

One might ask, couldn’t tool use under water grow to reach competitive exclusion first? Apparently not. Unlike air, water is a very dense and forceful fluid relative to the muscles of species that operate within it, gravity doesn’t hold down aqueous structures or animals very well, and language may not allow for the same degree of phonetic articulation underwater as well as it does in air. But underwater tool using collectives do exist. Dolphins use sponges in collectives, and the master observer Jacques Cousteau discovered in the 1980s that octopi used rocks as tools, in large socially imitative groups. Like their eyes and brains, two of their eight appendages are prehensile with bilateral symmetry, meaning they are specially neurologically wired to oppose each other in grasping and wielding objects, just like human arms and hands (developmental convergence). Octopi even occasionally built large groups of small huts for themselves out of rocks, but their collective rock use could not make them the dominant species under water, due to its harsher physics compared to air. Thus it seems very likely that runaway tool use must happen with very high probability on land first, on all Earth-like planets. Again, this developmental hypothesis will eventually be testable by simulation.

The universe, from this perspective, seems developmentally fated for the fastest-improving language-capable tool-using species to emerge on land, in a breathable atmosphere, not under water. This new selection environment of cultural evo-devo, selecting for more complex language and more useful social collectives, is sometimes called memetic evolutionary development, using Richard Dawkin’s concept of the meme as any elemental mentally replicating behavior or idea.

We must recognize that memetic change is always accompanied by another selection environment, technological evo-devo, which starts out very weak at first but becomes increasingly dominant, because our social ideas always lead to ways to use technologies (things outside our bodies) to achieve our goals, and those technologies inevitably become smarter, more powerful and more efficient than biological processes, which are very limited by the fragile materials (peptide bonds) from which they are made.

Susan Blackmore’s calls any elemental socially replicating technological form or algorithm a teme. So we must realize that both memetic and temetic evo-devo always go together in leading animals, on any Earthlike planet. Once these new replicators (social ideas/behaviors and technologies/algorithms) emerge, biological evo-devo (genetic and even epigenetic change) soon becomes so slow and modest by comparison that its further changes become increasingly future irrelevant, relative to memes and temes. As much as we love our ecosystem and should strive to protect it, it is where ideas and technologies are taking us today, not biology, that drives the future of our civilization.

In the years since Russell’s indecent proposal, hundreds of other scientists, including the paleontologist Simon Conway Morris (Life’s Solution, 2001 and The Deep Structure of Biology, 2008) have proposed that humanity’s most advanced features, including our morality, emotions, and tool use, have all been independently discovered, to varying degrees, in other vertebrate and invertebrate species on Earth. Let us at this point acknowledge but also ignore Conway Morris’s Christianity, as his particular religious beliefs are his own business, and are not relevant to his scientific arguments, as his secular critics should honestly acknowledge. According to Conway-Morris, if something catastrophic happened to Homo sapiens on Earth, it seems highly probable that another species would very quickly emerge to become the dominant “human” tool-users in our place. In other words, local runaway complexification seems well protected by the universe.

In evo-devo language, we can say there appears to be a developmental immune system operating, to ensure that human emergence, and re-emergence if catastrophes like the K-T meteorite occur, will be both a very highly probable and an accelerating universal event, on any Earth-like planet. Only the quality of our present transition to postbiological status seems evolutionary, based on the morality and wisdom of our actions. Our pathway to and our subtype of humanity may thus be special and unique, but our humanity itself, in many of its key features, seems to be a product of the universe, far more than a product of our own free choice. Learning to see, accept, and better manage all this hidden universal development, and in the process bringing our personal ego, fears, and illusions of control back down to fit historical reality, are among the greatest challenges humans face in understanding the true nature of the universe and our place in it.

Fortunately, these and other developmentalist hypotheses can increasingly be tested by computer simulation, as our computing technology, historical data, and scientific theory get progressively better. Run the universe simulation multiple times, and anything that appears environmentally dominant time and again, and any immunity that we see (statistical protection of accelerating complexity), is developmental. The rest, of course, is creative and evolutionary. To recap our earlier example, hexagonal snowflake structure will be developmental on all Earth-like planets with snow. But the pattern on each snowflake will be evolutionary, and unpredictably unique, both on Earth and everywhere else. Nature uses both types of processes to build intelligence.

In Evolutionary Development, the Universe is not just a Ladder of Nature (above), or a Random Experiment (standard Evolutionary theory), but some useful combination of the two simpler models.

Let me stress here that evolutionary development is no return to the Aristotelian scala naturae (Ladder of Nature, Great Chain of Being), where all important matter and process are predestined into some strict hierarchy of emergence. Only the developmental framework of universal complexification is statistically predetermined to emerge in evo-devo models, not the evolutionary painting itself, which is the bulk of the work of art. Remember the all-important differences in tissue microarchitecture and mental processes between two genetically (developmentally) identical twins. Nor is an evo-devo universe a Newtonian or Laplacian “clockwork universe” model, which proposes total physical predetermination, though it is a model with some statistically clockwork-like features, including the reliable timing of various hierarchical emergences throughout the universe’s lifespan and death, just as we see in biological development).

Consider that both the Aristotelian and Lapacian models of the universe are not real models of development (statistically predetermined emergence and lifecycle) but rather a caricature of development, one-sided views that allow no room or role for evolution. They are as incomplete in describing the whole of an evo-devo universe as neo-Darwinian theory is today.

Nor is an evo-devo universe the random, deaf-and-dumb Blind Tinkerer that universal evolutionists like Richard Dawkins (The Blind Watchmaker, 1996) or the writers of Mankind Rising portray. It appears that our universe is significantly more complex, intelligent, resilient, and interesting than all of these models suppose – it is predictable in certain critical parts that are necessary for its function and replication, and it is intrinsically unpredictable and creative in all the rest of its parts. Furthermore, unpredictable evolution and predictable development may be constrained to work together in ways that maximize intelligence and adaptation, both for leading-edge systems, and for the universe as a system.

Evo-devo biology is an academic community of several thousand theoretical and applied evolutionary and developmental biologists who seek to improve standard evolutionary theory by more rigorously modeling the way evolutionary and developmental processes interact in living systems to produce biological modules, morphologies, species, and ecosystems. Books like From Embryology to Evo-Devo, 2009, and Convergent Evolution: Limited Forms Most Beautiful, 2011, are great intros to this emerging field. I expect most evolutionary developmental biologists would agree with the statement that evolution and development are in many ways opposite and equally fundamental processes in complex living systems, and that neither can be properly understood without reference to its interaction with the other.

The best of this work realizes there are two key forms of selection and fitness landscapes operating in natural selection – evolutionary selection, which is divergent and treelike, with chaotic attractors, and developmental selection, which is convergent and funnel-like, with standard attractors. Thus evolutionary developmentalism is an attempt to generalize the evo-devo biological perspective to nonliving replicating complex adaptive systems as well, including solar systems, prebiological chemistry, ideas, technology, and in particular, to the universe as a system.

Let’s close this overview with one revealing example of the interaction of evolution and development. In biological systems, the vast majority of our genes, roughly 95% of them, are evolutionary, meaning they change randomly and unpredictably over macroscopic time, continually recombining and varying as species reproduce. Only about 3-5% of our genes control our developmental processes, and those highly conserved genes, our “developmental genetic toolkit“, direct predictable changes in the organism as it traces a life cycle in its environment. As I’ve argued before, as a 95%/5% Evo/Devo Rule, roughly 95% of the processes or events in a wide variety of complex adaptive systems, including organizations, societies, species, and the universe may turn out be creative bottom-up and evolutionary, and only 5% may be predictable top-down, and developmental, though this evo-devo ratio must surely vary by system to some degree. The generic value of a 95/5 Rule in building and maintaining intelligent systems, if one exists, would explain why the vast majority of universal change appears to be bottom-up driven, evolutionary and unpredictable in complex systems, what systems theorist Kevin Kelly called Out of Control in his prescient 1994 book. Yet a critical subset of events and processes in these systems also appears to be top-down/systemically directed, developmental, and intrinsically predictable, if you have the right theory, computational resources, and data. Discovering that developmental subset, and differentiating it from the much larger evolutionary subset, will make our world vastly more understandable, and show how it is constrained to certain future destinies, even as creativity and experimentation keep growing within all the evolutionary domains.

So what do we gain from conditionally holding and exploring the hypothesis of universal evolutionary development? Quite a lot, I think:

First, we regain an open mind. Rather than telling humanity’s history from a dogmatic and one-sided perspective, and assuming that our past existence in the universe is predominantly a “random accident,” we remember that there are many highly predictable things about our universe, such as classical mechanics, the laws of thermodynamics, and accelerating change. This allows us to present life’s story as a mystery: What parts of its emergence are very highly probable, or statistically predetermined? What parts are improbable accidents? We lose our blind faith that neo-Darwinism explains all of life or the universe, and we realize that there appears to be a balance between evolutionary experiment and developmental predetermination in all things in the universe, as in life.

Second, we regain our humility. We no longer see ourselves as either miraculous creations or extremely improbable accidents. We recognize that there are likely vast numbers of human communities in the universe, which has self organized to produce complex systems like us, and our postbiological descendants. It is commonly suggested that we are incredibly unique in the universe, and that we emerged “against astronomical odds.” On the contrary, developmentalists suspect that many or all of the things we hold most dear about humanity, including our brains, language, emotions, love, morality, consciousness, tools, technology, and scientific curiosity, are all highly likely or even inevitable developments on Earth-like planets all across the universe. This kind of thinking, looking for our universals as well as our uniquenesses, moves us from a Western exceptionalism frame of mind to one that also includes an Eastern or Buddhist perspective. We may not only be unique and individual experiments, but we may also be members of a type that is as common as sand grains on a beach, instruments of a larger cycle of universal development and replication.

Third, we lose our unjustified fearfulness of and pessimism toward the future, and replace it with courage and practical optimism. The evolutionary accident story of humanity teaches us to be ever vigilant for things that could end our species at any moment. Vigilance is adaptive, but fear is usually not. We are constantly reminded by evolutionists that 99% of all species that ever lived are extinct (yes, but they were all necessary experiments, and their useful information lives on), and we live in a random, hostile and purposeless universe (no). Evolutionists conveniently forget that the patterns of intelligence in those species that died are almost all highly redundantly backed up in the other surviving organisms on the planet. Life is very, very good at preserving relevant pattern, information, and complexity, and now with science and technology, it is getting far better still at complexity protection and resiliency. When we study how complexity has emerged in life’s history, we gain a new appreciation for the smoothness of the rise of complexity and intelligence on Earth. Every catastrophe we can point to appears to have primarily catalyzed further immediate jumps in life’s accelerating intelligence and adaptiveness at the leading edge. Life needs regular catastrophe to make it stronger, and it is resilient beyond all expectation. What causes this resilience? Apparently a combination of evolutionary diversity and developmental immune systems, and we still undervalue the former, and are mostly ignorant of the latter. If the universe is developmental, we can expect it has some kind of immune systems protecting its development, just as living systems do. The more we are willing to consider the idea that the universe may be both evolving and developing, the more we can open our eyes to hidden processes that are protecting and driving us toward a particular, predetermined future, even as each individual and civilization on Earth and in the universe will take its own partly unpredictable and creative evolutionary paths to that developmental future.

Fourth, we gain an understanding of universal purpose. Talk of purpose legitimately scares most scientists, who are so recently free of religion interfering in their work. They claim they don’t want to return to a faith-based view of the world, but we all must have, and should constantly revise and keep parsimonious our own personal set of faiths (for example, our scientific axioms), as human reason and intuition, no matter how powerful they become, will always be computationally incomplete. Unexamined faiths are of course the most dangerous kind. Evolutionists put a lot of unexamined and unrecognized faith in their purposeless universe model, so much that it can blind them to the value of admitting and exploring the unknown. Many scientists attack hypotheses of universal teleology wherever they find them – even as they live in a world that they clearly know is predictable in part. We must call that stance hypocrisy, as predictability is a basic form of teleology, or purpose. Evolutionary and behavioral psychologists are now proposing biologically-inspired scientific theories of human values. I recommend The Moral Landscape, by Sam Harris, 2011, which I’ve reviewed earlier. But most of this work still is not deeply biologically-inspired, as it remains focused on evolution, ignoring development. We must recognize that a better understanding of universal evolution and development can help science derive more useful and more universal evolutionary and developmental values. I believe it is both the best definition and the purpose of humanity to use technology to continually reshape us, individually and collectively, into something more than our biological selves, and to do this in as deliberate and ethical a way as possible, using both evolutionary and developmental means. We can further realize that it appears to be our universal purpose to think, feel, act, and build in ways that maximize our intellectual and emotional intelligence, advancing our minds and hearts.

Fifth, we recognize that very important parts of the future are predictable. This benefit is the most useful to me as a professional futurist. Increasingly, we find foresight practitioners who accept the likelihood of developmental futures. Consider Pierre Wack at Royal Dutch/Shell’s foresight group, who proposed the inevitable TINA (There Is No Alternative) trends in economic liberalization and globalization in the 1980’s. Or Ron Inglehart and Christian Welzel, who have charted the inevitable developmental advance (with brief and partial evolutionary reversals) of evidence-based rationalism and personal freedom in all nations over the last 50 years. Some leading recent books arguing for the inevitability of certain kinds of social development are Robert Wright’s Nonzero, 2000 (on positive sum rulesets), Steven Pinker’s The Better Angels of Our Nature (on violence reduction) and Ian Morris’s, The Measure of Civilization, 2013 (on the predictable dominance of civilizations that are leaders in energy capture, social organization, war-making capacity, and information technology). There are still far too many professional futurists who confidently and ignorantly claim that the future is entirely evolutionary (“cannot be predicted”). But a growing number of leaders, strategists, and futurists see regionally and globally dominant trends and inevitable convergences, make good predictions, and use increasingly better data and feedback to improve their models.

For a good recent book on this, read Nate Silver’s excellent The Signal and the Noise: Why So Many Predictions Fail But Some Don’t, 2012. As we learn take an evolutionary developmentalist perspective, at first unconsciously and later consciously, we will greatly grow our predictive capacity in coming decades. More of us will foresee, accept, and start managing toward the ethical emergence of such inevitable coming technological developments as the conversational interface and big data, deeply biologically-inspired (evo and devo) machine intelligence and robotics, digital twins (intelligent software agents that model and represent us) and the values-mapped web, lifelogs and peak experience summaries, the wearable web and augmented reality, teacherless education, internet television, and the metaverse. Professional futurists and forecasters are now developing our first really powerful tools and models that will keep expanding our prediction domains and horizons, and improving the reliability and accuracy of our forecasts. I believe evolutionary developmentalism is a foundational model that all long range forecasters and strategists need to embrace. Not only must we realize there are possible and preferable futures ahead of us, but we must be convinced that there are inevitable and highly probable futures as well, futures which can increasingly be uncovered as our intelligence, data, and methods improve. Such an effort, at a species level, is the only way we can map what remains truly unpredictable, at each level of our collective intelligence.

We’ve got a long way to go before modern science is willing to give the developmentalist perspective the same consideration and intellectual honesty that we presently give the evolutionist perspective. A lot of papers will have to be published. A lot of arguments will have to be made, and evidence marshaled. Courageous scientists will have to build the bridge from the developmentalist aspects of physics, chemistry, and biology to the highest aspects of our humanity, our ethics, consciousness, purpose, and spirituality. Convergent Evolution is one of several fields that will win lots of converts to developmentalism as it advances. Astrobiology will likely also play a big role, if it shows us just how common our type of life is in the universe, as many suspect it will.

Fortunately, as futurist Alvis Brigis noted to me in a recent conversation, many of the world’s leading companies are already surprisingly developmentalist in their strategy and planning. We can trace this shift back at least to Pierre Wack’s strategy group at Royal Dutch/Shell in the 1980’s, as discussed in Peter Schwartz’s The Art of the Long View, 1996, a classic in business foresight. Wack realized that in order to do good scenario planning (exploring “what could happen”, and the best strategic responses to major uncertainties) one should first constrain the possibility space by understanding what is very likely to continue to happen in the larger environment. To restate this in evo-devo language, Wack recommended starting with developmental foresight (finding the apparently “inevitable” macrotrends), and then doing evolutionary foresight (exploring alternative futures) within a testable developmental frame. Treating both evo and devo foresight perspectives seriously is a key challenge for strategy leaders. Many management and foresight consultancies are good at one, but not the other, as it’s a lot easier to pick one perspective as your dominant framework than to have to continually figure out how to integrate two opposing processes. Yet both are critical to understanding and managing change.

I do technology foresight consulting for several companies, and follow foresight work at the consultancies, and I’m convinced that those companies with the best predictions, forecasts, and foresight processes interfacing with their strategic planning groups are winning increasingly large advantages in their markets every year. All the most successful companies realize there are many highly predictable aspects of our future, and collectively our business and government leaders are now betting trillions annually on their predictions. A few are using good foresight processes, but most are still flying by the seat of their pants.

The executives leading our most successful companies don’t see the world as a random accident, like an evolutionist, or some naive and self-absorbed postmodernist who lives off the exponentiating wealth and leisure of the very same science and technology that he argues are “not uniquely privileged perspectives” on the universe. Let’s hope our young scientists in coming years have the courage to be as developmentalist in their research, strategy, and perspective as our leading corporations are today. And as our biologically-inspired intelligent machines, destined to be faster and better at pattern recognition than us, will be a few decades hence. Will modern science recognize the evolutionary developmental nature of the universe before human-surpassing machine intelligences arrive and definitively show it to us? That is hard to say. But I believe we can predict with high probability that as mankind continues its incredible rise, our leaders, planners, and builders must become evolutionary developmentalists if we are to learn to see reality through the universe’s eyes, not just our own.

Further Reading

For a more detailed treatment of evolutionary developmentalism, with references, you may enjoy my scholarly article, Evo Devo Universe?, 2008 (69 pp. PDF), and for applications of evo-devo thinking to foresight, Chapter 3, Evo-Devo Foresight (90 pp.), of my online book, The Foresight Guide, 2018.

For a speculative proposal on where accelerating change may take intelligence, as a universal developmental process, see my paper The Transcension Hypothesis, 2012 (and the lovely 2 min video summary by Jason Silva). This hypothesis speculates, and offers preliminary evidence and argument, that black holes may be developmental attractors for the future of intelligent life throughout the universe.

I wish you the best in your own foresight journey, and that your thoughts and actions help you, your families, and your organizations to evolve and develop as well, every day, as this amazing universe will allow.

Until

Until