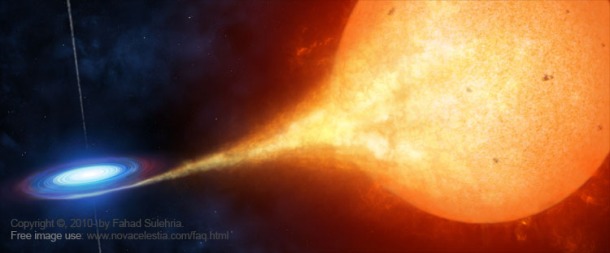

Low-mass X-ray binary (LMXRB) star system. Strange as it seems, Earth’s future may look something like this, with us inside a black hole-like environment of our creation, on a highly accelerated path to merging with other universal civilizations doing the same. If true, our destiny is density, and dematerialization.

This post is a followup to a popular paper of mine on three big topics: the Fermi paradox, accelerating change, and astrosociology (the nature and goals of advanced civilizations). The paper is called The transcension hypothesis: sufficiently advanced civilizations may invariably leave our universe, and implications for METI and SETI. It was published in Acta Astronautica in 2012.

Speculation on the Fermi paradox has grown considerably in the last two decades, as it has become increasingly obvious that we live in a universe that is very likely to be teeming with Earth-like planets, and also with intelligent, curious, and technologically accelerating forms of life. When we extrapolate our own accelerating progress in science, IT, and nantechnologies, we can imagine that any one of these civilizations could easily send out self-replicating nanotech that would spread across our Milky Way galaxy and beam the information that it finds out to the rest of the universe (or alternatively, just back to the originating civilization), creating a Galactic Internet, and making our universe as information-transparent as our planet is becoming today. Our galaxy has a radius of 100,000 light years. Replicating nanotech, traveling at just 5% of light speed, which we can imagine building even today, could reach all corners of our galaxy in 2 million years. So if other Earth-like planets and their intelligent life likely emerged, closer to the center of our galaxy, at least one billion years before ours did, as several astrobiologists have estimated, and any one of them could have easily expanded, why don’t we see any signs of this Galactic Internet today? Or signs of past alien visitation, probes, and megastructure beacons near Earth? Or signs of intelligent structures or civilizations anywhere in the night sky? In other words, Where is Everybody? That’s the Fermi paradox.

In a nutshell, the transcension hypothesis predicts constrained transcension of intelligence from the universe, rather than expansion (colonization) within the universe by intelligence, wherever it arises. If the hypothesis is correct, the reason we don’t see and haven’t heard from advanced civilizations anywhere is that the vast majority leave the visible universe as they develop, and the few that do not are very unlikely to be visible to us, with our presently weak SETI abilities. That’s a very strong claim. Could it be right?

My paper makes a series of assumptions about the nature and future of intelligent life in our universe. Most of these key assumptions may need to to be correct, in some fashion, for the hypothesis itself to be correct. A few colleagues have asked me to summarize these assumptions in one place, so here they are. This list is a good way to get a quick summary of the hypothesis as well.

Here are the key assumptions of the transcension hypothesis, as I presently see them:

- Intelligent life, on Earth and elsewhere in our universe, is not only evolving (diversifying, experimenting), but also developing (converging toward a particular set of future destinations, in form and function), in a manner in some ways similar to biological development. In other words, all civilizations in our universe are “evo-devo” both evolutionary and developmental. The phenomenon of convergent evolution tells us a lot about the way development may work on planetary scales. A kind of cosmic convergent evolution (universal development) must also exist at universal scales.

- The leading edge of intelligence always migrates its brains and bodies into increasingly dense, productive, miniaturized, accelerated, and efficient scales of Space, Time, Energy, and Matter (what I call STEM compression), because this is the best strategy to become the niche-dominant local intelligence (and for modern humans, Earth’s biosphere is one precious and indivisible niche), and because the special physics of our universe allows this continual migration into “nanospace“. Human brains with their thoughts, emotions, morality, and self- and social-consciousness, are the most STEM-compressed higher computational systems on Earth at present. But our biological brains are just now starting to get beat at the production of intelligence by deep learning computers, which are even more profoundly STEM-compressed in certain kinds of computation than neurons (for example, electrical interneuron communication in an artificial neural network is seven million times faster than chemical action potentials between biological neurons). Once today’s weakly bio-inspired machine intelligence becomes fully self-improving, it seem likely to continue growing and improving at rates that make biological intelligence appear rooted in spacetime by comparison, in the same way that Earth’s plant life appears rooted in spacetime by comparison to self-aware animal life. Fortunately, accelerating STEM-compression of both human civilization and of our leading computational technologies is stepwise measurable and testable, as argued in my paper. Our academics need better funding and training to do so, however. Measuring the STEM-efficiency growth of new computational platforms, like quantum computing, is today far more art than science.

- The acceleration of STEM compression must eventually stop, at structures analogous to black holes, which in current theories appear to be the most computationally accelerated and computationally efficient entities in the known universe, an insight Seth Lloyd made in 2000 which remains widely underappreciated by most information, computation, and complexity theorists today. Fortunately, this idea of a developmental “black hole destiny” for civilization seems quite testable observationally via search for extraterrestrial intelligence (SETI), as argued in my paper.

- A civilization whose intelligence structures are compressed to scales far below the nanoscale may well be capable of creating or entering black-hole-like environments without their informational nature being destroyed. There are 25 orders of magnitude in size between atoms and the Planck scale. This is almost as large a size range as the 30 orders of magnitude presently inhabited by life on Earth. We simply don’t know yet whether intelligence can exist at those small scales. My bet is that it can, and that STEM compression drives leading universal intelligence there, as the fastest way to generate further intelligence, with the least need for local resources.

- Due to general relativity, extreme gravitational time dilation occurs very near the surface (event horizon) of black holes. Thus black holes, wherever they exist, can act as forward time travel devices, for any highly STEM compressed civilization that can arbitrarily closely approach their surface without destroying itself. Black-hole-like conditions are thus gateways to instantaneous meeting and merger with other unique civilizations in our universe within any gravity well. Our gravity well includes the Milky Way and Andromeda galaxies, each of which is destined to merge all its black holes, and each of which may contain millions of intelligent civilizations. The rest of our universe is accelerating away from us, due to dark energy. Perhaps the vast majority of black holes in these galaxies (billions?) are unintelligent collapsed stars. But if the transcension hypothesis holds, some smaller number (millions?) may also be a product of intelligent civilizations.

- As local acceleration of STEM compression stops, the more black-hole-like we become, local learning will saturate. Local intelligence will be running as fast as it can in this universe, yet it will be both resource and speed constrained. It’s local conditions, in other words, will be increasingly boring and predictable. It will be, from its own reference frame, at “The End of Science”, the end of what it can easily learn and know, to use the title of the elegant and profound book The End of Science (1996/2015) by science writer John Horgan. In those interesting conditions, it may irresistable to slow down local time via black hole entry, and thus simultaneously accelerate nonlocal time, making meeting and merger with other civilizations near-instantaneous. In “normal” universal time, galactic black holes are predicted to merge some tens to hundreds of billions of years from now, as our universe dies. But from each black hole’s reference frame, this merger is near-instantaneous We can think of black holes as shortcuts through spacetime, just like quantum computers are shortcuts through spacetime. Indeed, quantum physics and black holes (relativity) must eventually be both evo (chaotically) and devo (causally) connected, both physically and informationally, in any future theory of quantum gravity. If some type of hyperspace, extradimensionality, or wormhole-like physics is possible, there might also be ways of future humanity instantaneously meeting civilizations beyond our two local galaxies. But such exotic physics is not necessary for our local gravity well, and for all other civilizations in their own galactic gravity wells. Standard relativity predicts that if we can survive in black-hole-like densities, and if our galaxies are life and intelligence-fecund, we will meet and merge with potentially millions of civilizations as soon as we approach the surface of any black hole, from our reference frame. In other words, our universe appears to have both “transcension physics” and massive parallelism of intelligence experiments built into its relativistic topology and large scale structure.

- If we live in not only a developmental universe, but an evolutionary one, each local universal civilization can never be God-like, but must instead be computationally incomplete, an evolutionary “experiment” with its own own unique discoveries and views on the meaning and purpose of life. Thus each civilization, no matter how advanced, would be expected to have useful computational differences, and be able to learn useful things, from every other civilization. In such a universe, we would greatly value communication, assuming that we could trust the other advanced civilizations that we might communicate with. Computational incompleteness would also make us increasing value simulation over physical experimentation, the more complex intelligence becomes. The better faster, better, and more resource (STEM) efficient models of our physical world get, the more we choose virtual rather than physical experiments to address perennial incompleteness in our intelligence.

- If not only intelligence, but also immunity (stability, antifragility) and morality grow in leading intelligences in our universe, in rough proportion to their complexity, in other words, if these three life-critical systems are each not only evolutionary, but also developmental, and thus their emergent form and function is at least partly encoded in the “genes” (initial conditions, laws, and environmental constraints) of the system itself, then we can predict that more advanced intelligences, including our coming deep learning computers, will be not only more intelligent, but also more immune and moral than we are today. This idea is called developmental immunity and developmental morality, and I explore it in my paper, Evo-Devo Universe? (2008). If these developmental processes exist, they tell us something about the nature of postbiological life. Such life is going to be a whole lot more collaboration-oriented, intelligence-oriented, immune, and moral than we are today. Social morality, for its part, pushes complex intelligences toward a more ethical impact on the world and each of its sentiences. Decreasing violence has been a mild trend in human societies in recent centuries, as documented in Pinker’s The Better Angels of Our Nature, 2011. But I expect it to be a much stronger trend in postbiological intelligences. Physicists Stephen Dick and Seth Shostak have stressed the importance of thinking hard about the norms and morality of postbiological culture. It’s a big assumption that surviving human and machine collectives must on average become increasingly intelligent, immune, and moral in proportion to their cognitive complexity, under natural processes of evolutionary selection and development, but this is where all the evidence seems to be leading, in my view.

- In a universe with developmental immunity and morality, a moral prime directive must emerge, a directive to keep each local civilization evolving in a way that maximizes its intelligence, uniqueness and adaptiveness prior to transcension. That means one-way messaging (powerful METI beacons), self-replicating probes able to interact with less advanced civilizations, and any other kind of galactic colonization would both be ethically prohibited by postbiological life, due to the great reduction in evolutionary diversity that would occur. Wherever it happened, we would meet informational clones of ourselves after transcension, a most undesirable outcome. In biology, evolution keeps clonality a very rare outcome, due to the diversity and adaptiveness cost that it levies on the progeny. In such an environment, any future biological humans that wanted to continue to colonize the stars would be prevented from doing so, by much more ethical and universe-oriented postbiological intelligences. That is assuming biological organisms even continue to be around after postbiological life emerges. Due to STEM compression, their status as biologicals would likely be vanishing short, once they invent technology capable of colonization. It seems much more likely that biology develops into postbiology, relatively soon (just a few centuries perhaps) after digital computers emerge, everywhere in the universe. This outcome also seems likely to be testable via future information theory and SETI, as I argue in my paper.

- Some physicists, most notably Lee Smolin in his hypothesis of cosmological natural selection, propose that black holes may be “seeds” or “replicators” for new universes. That gives us a clue to what we might do after we meet up with other cosmic intelligences. We would likely compare and contrast what we’ve learned, and then seek to make a better and more adaptive universe (or universes) in the next replication. Current physics and computation theory suggest that our universe, though vast, is both finite and computationally incomplete. It may have gained its current amazing levels of internal complexity in the same way life on Earth got its amazing living complexity, via evolutionary and developmental (“evo-devo“) self-organization, through many past replications, in some kind of selection environment, a “multiverse” or “hyperverse.”

- If all of this is roughly correct, our future isn’t outer space, it’s “inner space.” Both the inner space of black-hole like domains, and the inner space of increasingly virtual and computational domains. The lure of our continually improving inner space is why 21st century folks spend so much time (too much time!) interacting with our still-dumb mobile devices today. It is why the growth of virtual and augmented reality heralds far more than just better entertainment experiences. Combined with the growth of machine learning, virtual/augmented reality will increasingly become the thinking, imagination, and simulation space for eventual postbiological life. Virtual space is where intelligent machines will figure out what they want to do in physical space, just as our own simulating brains are biology’s virtual reality. And just like humans have have done as our civilization has developed, future machines will do more and more internalization, or thinking in virtual space, and less and less external acting, in physical space, the more intelligent they get. This internalization process has a name. It’s called dematerialization (both economic dematerialization and product and process dematerialization), the substitution of information and computation for physical products, processes, and behaviors. The futurist Buckminster Fuller called this process ephemeralization. But ephemeralization of intelligence is only half the story. It describes dematerialization, not densification. If the transcension hypothesis is true, the developmental destiny of all complex life is both accelerating “densification” (eventually to a black hole-like state) and “dematerialization” (becoming increasingly informational and virtual, over time). See my online book, The Foresight Guide, for more on these planetary megatrends, densification and dematerialization (“D&D”) and how they appear to drive universal accelerating change.

As Fermi paradox scholar Stephen Webb says at his blog, this is quite a lot of “ifs!” Disproving any of these assumptions would be a good way to start knocking aspects of the transcension hypothesis out of contention. We would learn a lot about ourselves and the universe in the process, so I really hope that each of these gets challenged in coming years, as the hypothesis gets further exposure and critique.

Webb is the author of Where is Everybody?, 2015, a book that offers seventy-five possible solutions to the Fermi Paradox. Webb did a great job condensing the transcension hypothesis into just three pages in his book. His 2002 edition didn’t include it, as I published my first paper on the hypothesis in mid-2002. At Webb’s blog, he charitably says the transcension hypothesis is “one of the most intriguing” possible solutions that he has seen. He also observes that “Unlike so many “solutions” to the Fermi paradox, this one offers avenues for further research.” It certainly does, which is why I hope it continues to gain scrutiny and critique.

A few scholars are now citing the transcension hypothesis in their academic papers on the Fermi paradox and accelerating change, including Sandberg 2010, Flores Martinez 2014, and Conway Morris 2016. I am hoping that trend continues. The more attention it gets, the more critique it will get.

Perhaps the strangest and hardest-to-believe part of the transcension hypothesis, for many, is the idea of universal development. It is particularly relevant to the first, seventh, eighth, and ninth assumptions above. The most amazing and odds-defying thing I’ve come across in my own study of the natural world so far is the process of biological development. Most people don’t think about both how wonderful and how improbable, on its face, is the process of organismic development.

Think about it. Development is guided by a small handful of genes in our genome. It’s incredible that it works, yet it does, and it made you! Development is a good candidate for the most incredible process in the known universe. In many ways, development is even more surprising than evolution, which I define as the set of biological genes and mechanisms that create unpredictable experiment and variety, as opposed to that small subset of chaos-reducing biological genes and mechanisms that statistically guarantee a hierarchical set of future-specific forms and functions. Standard evolutionary theory requires development as an organismic process, yet it also treats development as subservient to the variety-generating processes in natural selection. That second assumption is incorrect, in my view, and it has led us down the wrong path in long-range thinking on the future of complex adaptive systems. We view our complex future as far less developmentally constrained than it actually is.

Fortunately, a growing contingent of evo-devo biologists argue that development’s long-range role in constraining the possibilities of evolutionary change may be equally important to evolution’s long-range impact on development. Both processes seem fundamental to mature theory of adaptation. Ecologists have published good work on the way ecosystem development limits the future of evolutionary processes. For example, think of ecological succession, in which increasing senescence of the ecosystem limits short-term evolutionary variety, while also making the oldest parts of the system increasingly vulnerable to death (and renewal). Think also of niche construction, which tells us how growing intelligence, which we use to fashion comfortable niches, limits the future selection placed upon us by our environment. Scholars of convergent evolution also describe apparently universal processes of morphological and functional development that will constrain evolutionary possibilities on all Earth-like planets. Cosmologists who take fine-tuned universe arguments seriously also talk about both local variety and processes of universal development, though they don’t often use that clarifying phrase, when they describe physical and chemical constraints on the possibilities of evolutionary change. All these are important clues toward a meta-Darwinian, evo-devo universe paradigm of universal change.

In short, if our universe actually replicates, as seems plausible in several cosmology theories, and if it exists in some kind of larger selection environment, as also seems plausible, then not only evolution, but development (“convergent evolution”) must also occur not just in species forms and ecosystems, but for our increasingly intelligent planet, as a developing life-human-machine “Global Superorganism”, and for our entire universe itself, as a replicator in the multiverse. Certain aspects of the future of complex systems must be statistically highly biased to converge on particular destinations, and today’s evolution-centric science still has a lot of growing up still to do in order to see these destinations. It needs to become “evo-devo”, seeing the contributions of both evolution and development to the future of universal complexity.

The paper’s second key assumption, STEM compression is more palatable to most people, in my experience, and may turn out to be the most enduring contribution of the paper, even if the rest of the hypothesis is eventually invalidated. If you’ve heard of nanotechnology, you know that life’s leading edge today, humanity, is doing everything it can to move our complexity and computation down the smallest scales we can. We have been very successful at this shrinking over the last several hundred years, and our ability to miniaturize and control processes at both atomic and subatomic scales is growing exponentially. In fact, human brains themselves are already vastly denser, more efficient, and more miniaturized computational devices than any living thing that has gone before them. But they are positively gargantuan compared to the intelligent computing devices that are coming next.

Fortunately I think each of the key assumptions outlined above are testable, though some are obviously more testable than others in today’s early stages of astrophysical theory, SETI ability, information, complexity, and evo-devo theory, and simulation capacity. If anyone is doing work that might shed light on any of these assumptions, I would love to hear of it.

You can find my paper here: The Transcension Hypothesis, 2012. See also this fun 2 minute YouTube video of the hypothesis, by the inspiring futurist Jason Silva and Kathleen Lakey, which has raised its visibility in recent years.

You can find an overview of the evo-devo (evolutionary and developmental) universe hypothesis in my chapter-length article, Evo-Devo Universe? A Framework for Speculations on Cosmic Culture, 2008.

Comments? Critiques? Feedback is always appreciated, thanks.